There is always a cost for certainty, but is this reasonable?

The cost of balancing the electricity network is increasing, and becoming more volatile,. It is cost that all consumers pay. But how big should the premium for cost certainty be?

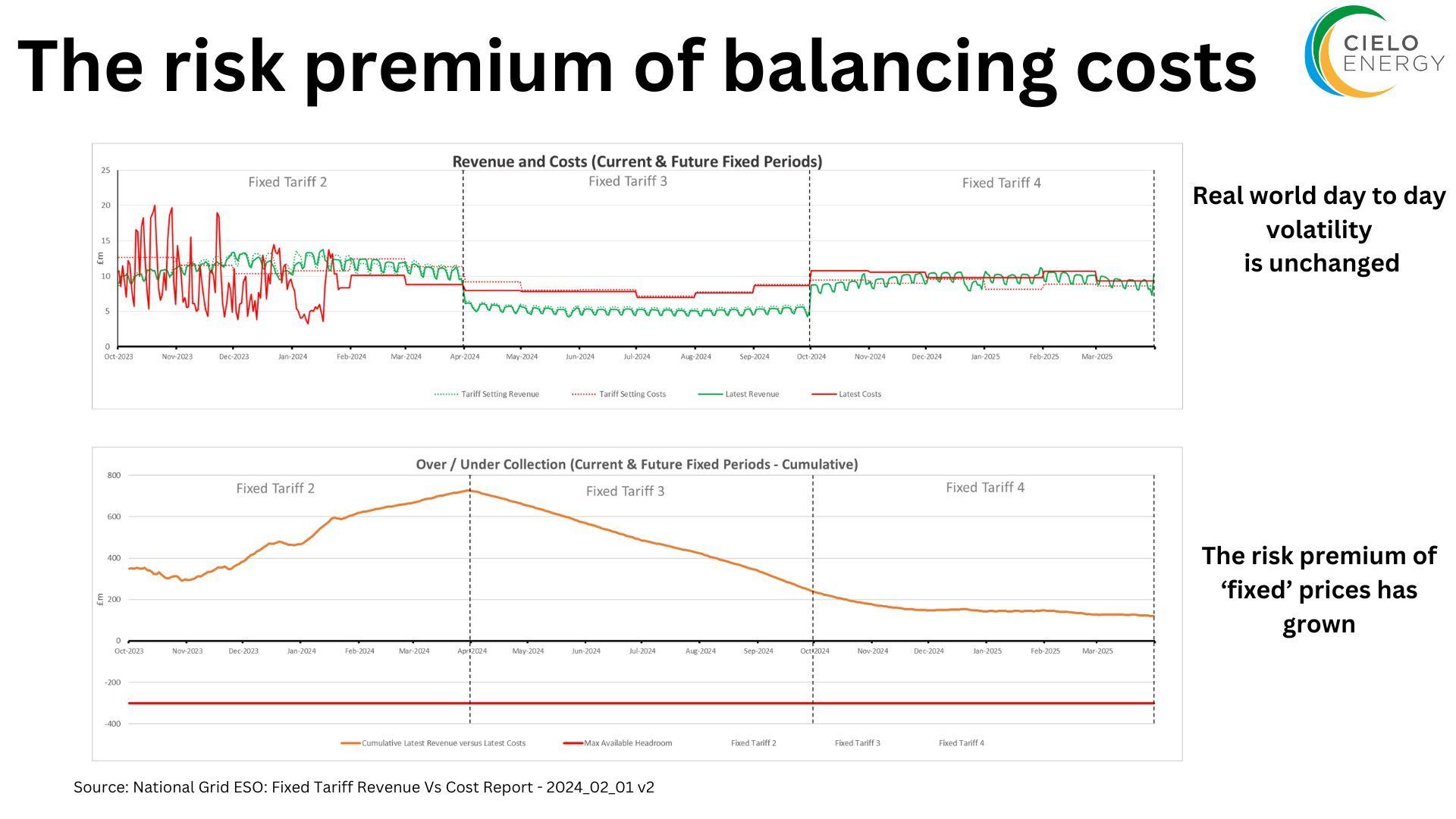

Based on data published by National Grid in January, the current over recovery of income compared to costs if £500M, equivalent to around £5 for each domestic customer.

After huge increase in balancing costs from a price equivalent of around £4/MWh a few years ago to £14/MWh recently, there was general consensus that something needed to be done.

Managing this increase, along with the inherent real-time variability was becoming a real issue, so something had to be done – but is this a reasonable something?

A brief history of balancing costs…

Balancing costs (BSUoS) covers the actions taken by National Grid to ensure security of supply in real time. This means that sometimes costs are low while at times of system stress they are high. These costs are added together and passed to market participants on a cost per unit basis.

Following a modification as part of Ofgem’s Targeted Charging Review (TCR), it was deemed that these costs should fall only on consumption, rather than both sides of the market has been previously. The economic theory of this is that it should reduce prices overall (reality is probably somewhat different).

As balancing costs were becoming more and more volatile suppliers were struggling to price the risk effectively so two contract solutions emerged.

1) Suppliers warehouse the cost, and charge consumers for the risks being held (fixed contracts)

The variability in costs was becoming too large without a significant risk premium being added; which savvy customers, or their advisors, thought too large (whether it was or not is another issue entirely)

2) Suppliers charge consumers on a pass-through basis; exposing end customers directly to the cost associated with their demand. (Pass-through contracts)

This approach simply passes the costs straight through to end users. Removing the premium, and the stability.

In a parallel approach, following the TCR balancing costs as charged between National Grid and suppliers are now fixed for 6 month periods, removing the volatility from suppliers – but it has not left the market!

The costs of balancing in 2024

Following the change National Grid now provides a fixed price for each 6 month period, but based on numbers released at the end of January is sitting on a premium of over £500 Million for this service (see the graph below). That is the amount of payments made compared to the actual cost of the service.

In theory this should be returned to consumers in future periods, but 80% of this is not forecast to be returned until well into 2025, and even then NGESO will be sitting on over £100M as a buffer. This is something that suppliers would have been vilified for in similar circumstances.

Is this the solution…?

The current approach means everybody is paying the same price, and in effect the same premium.

Passthrough contracts are no longer a reduced rate when compared to fixed price.

Having tried to manage balancing costs, it was certainly untenable in its previous form and something needed to be done.

But is it worth £500M premium across the market? In effect this is another pocket of customer money being used to underwrite system costs – to be added to the CfD, Capacity (and presumably hydrogen soon).

While it is certain that the cost of balancing the changing system is getting higher, and the amount of cash required to make it work is enormous.

Share this on social media